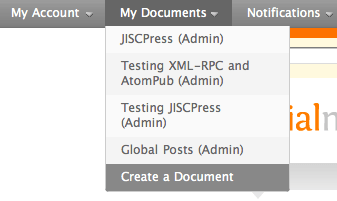

We finished JISCPress. If you’re interested, I’ve written a long overview of the work we’ve done with WPMU as a document discussion platform, based on WriteToReply. You’ll see that the project has, among other things, produced three plugins: digress.it, and two Linked Data plugins that run as background services across the platform, create relationships between documents and document sections and post RDF to the Talis Data Store. Fancy!

Category: Software

Scholarly publishing with WordPress

Working on the JISCPress project, I’ve been thinking quite a lot about scholarly publishing on the web, and in particular with WordPress. This morning, I read a post over on the ArchivePress blog about some WordPress plugins which are useful additions for creating a scholarly blog and it got me thinking a bit more about what features WordPress would need to support scholarly publishing.

JISCPress does away with the idea that WordPress is a blogging tool, and instead uses WordPress Multi-User as a document publishing platform, where one site or ‘blog’ is a document. The way WPMU is structured means that despite serving multiple (potentially millions) of document sites, the platform remains relatively ‘lightweight’ as each document site generates just a handful of additional database tables, while sharing the same administrative core as a single WordPress install. So, 100 WordPress blogs on WPMU is nothing like the equivalent of running 100 separate WordPress blogs, both from the point of resource requirements and administration. In fact, quite soon, there will be no such thing as WPMU as the two products are going to be merged and because they share 90%+ of the same code already, it’s not too difficult to achieve. ((Has anyone done a diff on the two code bases to measure exactly what percentage of the code is shared between WP and WPMU?))

Anyway, my point here is to discuss whether WordPress can be extended to accommodate most conventions found in scholarly publishing and where it is lacking, to identify the development work required to meet the needs of most academic who wish to write on and publish to the web. ((Actually, I think I’ll save the discussion of its shortfalls for my next post. This one is already long enough.))

Scholarly publishing extends to a wide variety of published outputs. As a Content Management System (CMS) and technology development platform, I believe that WordPress has the potential to support any type of scholarly publishing that the web supports. It is extremely extensible, as can be seen from the 6000+ plugins that are available. However, what I’m interested in is what can be done now, by an academic wishing to publish their work through the use of WordPress acting as a CMS. What can be achieved with a few quid ((I pay $5/year for my domain name and as many sub-domains as I need. I pay $10/month for my hosting with unlimited storage and bandwidth.)) to self-host WordPress so that a few plugins can be installed and a well structured, typical, scholarly paper can be published.

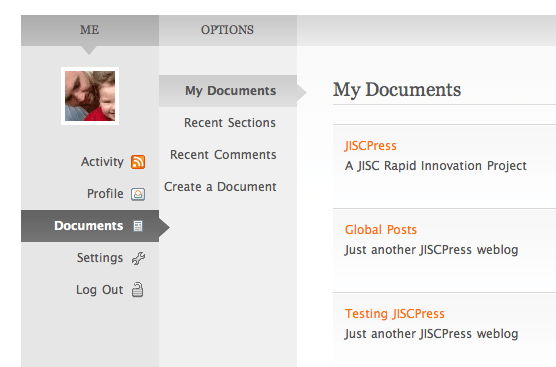

My Dissertation

For some time, I’ve been meaning to publish my MA dissertation. Back in 2002, I undertook some unique research which has not, to my knowledge, been repeated and I think there is some value in having it easily accessible on the web. I have an OpenOffice file and a PDF and, in the course of a morning, have published it under my own domain. The reason I did not publish it on the university WPMU platform is because I have been experimenting with different plugins and did not want to install plugins that were untested or we may not support long-term. In this case, I’ve used a single WordPress installation, but ideally an individual researcher, group of researchers or research institution, would run a WPMU installation which allowed multiple documents to be authored individually or collaboratively ((Like any decent CMS, WordPress supports role-based authoring and editing and maintains a revision history of edits, auto-saved once per minute. Revisions can be compared alongside of each other.)) and published directly to the web as XHTML.

BuddyPress, by the way, can make the experience even more natural, not only because it is based around a community of like-minded people writing together on the same web publishing platform, but also because, with a few tweaks here and there, we can move away from the language of blogs and towards the language of documents.

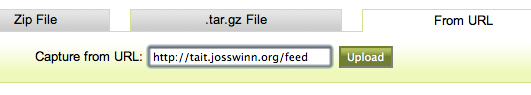

Enough of BuddyPress on WPMU for now and back to my dissertation. I set up the site in ten minutes, without using FTP or a command line because I use a host that provides a one-click install of WordPress and WordPress allows you to search for and install plugins from its Dashboard, rather than having to use FTP. Once the site was installed, I then made some basic changes to the settings, turning on XML-RPC and AtomPub, so that, if I decided to, I could publish to the site using my Word Processor. ((On a scholarly WPMU installation, plugins could be pre-installed and activated, a default theme selected and settings tweaked so very little work is required by the academic author prior to writing her document.)) I didn’t use this in the end, but trust me, it works very well using recent versions of MS Word, Open Office (free) and other blogging clients such as MS Live Writer (free).

So, what are the common characteristics of an academic paper? What does WordPress have to support to provide functionality that meets most scholars’ publishing requirements? I scratched my head (and asked on Twitter) and came up with the following:

- footnotes/endnotes

- citations

- use of LaTeX (sciences)

- tables

- images

- bibliography

- sub-headings

- annexes

- appendices

- dedication

- abstract

- table of contents

- index to figures

- introduction

- exposition

- conclusion

Many of these are supported in WordPress by default and don’t require any additional plugins (tables, images, sub-headings, annexes, appendices, dedication, abstract, introduction, exposition, conclusion, are all either basic literary conventions or just part of a simply structured document).

For additional support, I installed digress.it, which we have funded through the JISCPress project. This is a WordPress plugin which allows readers to comment on the paragraphs of a document, rather than at the document section level. We’re adding a lot more functionality to meet the objectives of the JISCPress project, but I chose digress.it, principally for the reason that it is designed to turn a WordPress blog into a document site. I could have used any other WordPress theme, but digress.it automatically creates a Table of Contents and allows you to re-order WordPress posts when they are read so that you don’t have to author your document in reverse or adjust the publication dates so the document sections appear in the correct order.

I added the abstract for my dissertation to the ‘about’ page, so it shows up on the front of the site. I also uploaded a PDF version so that people can download it directly. You’ll see that I also added some links to a related book and DVD, which will certainly appeal to people who are interested in my dissertation. The links pull an image and some basic metadata from Amazon, using the Amazon Machine Tags plugin. This could be used to link to the book in which your article is published and earn you money in click referrals. An alternative, would be the Open Book Book Data plugin, which retrieves a book cover and metadata from Open Library, where your book may already be catalogued. If it’s not on Open Library, catalogue it!

After setting this up, I installed a few more plugins:

Dublin Core for WordPress: Automatically adds ten Dublin Core metadata elements to the document mark up.

wp-footnotes: This allows you to easily add footnotes to your document by enclosing your footnote in double parentheses. ((I am using the plugin on this blog!))

OAI-ORE Resource Map: Automatically marks up the document sections with a OAI-ORE 1.0 resource map.

Google Analyticator: Adds Google Analytics support so you can collect statistics on the readership of your document.

WP Calais Archive Tagger: Analyses your entire document and automatically keywords each section, using the Open Calais API.

Search API: WordPress comes with search built in, but there is a new search API which will eventually make its way into the WordPress core. I’ve installed the plugin to provide full-text search across the document. It can also add Google Search to your document site.

wp-super-cache: This is simple to install and will significantly speed up your document site, making it a pleasure to navigate through and read 🙂

Plugins I didn’t use

wp-latex: Although I didn’t need it for my dissertation, it’s worth noting that WordPress supports the use of .

Academic Citation: You need to add a line of code to your theme for this to display. It supports the concept of an article being a single blog post, rather than a ‘document site’ and displays a variety of citation formats for readers to use.

Do you know of any other plugins for a scholarly blog?

The Beauty of Feeds

The other useful thing about managing a document using WordPress and in particular, using digress.it, is that you automatically get RSS/Atom feeds for the document. I’ve already discussed these in detail. It means that I was able to read my document in my feed reader, with footnotes and images displayed correctly.

See how nicely the formatting is preserved. is also rendered correctly in feed readers.

You’ll see that the document sections are listed in order; that is, first section on top. As I noted above, blogs list posts in reverse (most recent first), so I sorted the feed items in Yahoo Pipes and sorted it in ascending order. Yahoo Pipes exports as RSS and it’s that feed that I subscribed to in Google Reader. Wouldn’t it be nice, if I could import my document feed into an Institutional Repository? Wait a minute, I can! 🙂

When importing the default feed, the HTML output is accurate but in reverse order, while the RSS output from Yahoo Pipes didn’t import into EPrints very cleanly at all. I’ll work on this. UPDATE: Forget Yahoo Pipes. WordPress feeds can be sorted with a switch added to the URL: http://example.com/feed/?orderby=post_date&order=ASC

So there it is. An academic paper, published to the web using a modern CMS which supports most authoring and publishing requirements. I would favour an institutional WPMU platform for academics to author directly to, publish their pre-print to the web for open access and detailed comment, and import their RSS feed into the repository. As a proof of concept, I’m quite pleased with this. We are currently developing a widget that can be embedded in a web page or WordPress sidebar and allow a member of staff to upload a document or zipped folder of documents to the Institutional Repository. I wonder if we can also support the import of a feed from the widget, too?

So, what would your requirements be? Tell me and I’ll do my best to test WordPress against them.

JISCPress: Developing a community platform for the JISC funding process

I’m very pleased to announce that my bid with Tony Hirst at the Open University, to develop a community platform for the JISC funding call process based on WriteToReply, was successful. The original bid document is publicly available and currently offers the most information on this six month, £32,500 project.

Note that this is an open project using open source software and we welcome volunteer contributions from anyone. I’ve set up a project blog, mailing list, wiki and code repository. Feel free to join us if this WriteToReply spin-off appeals to you. If you know anyone that might be interested, please do let them know.

If you’ve been following WriteToReply, you’ll know that we use WordPress Multi-User and CommentPress. Eddie Tejeda, the developer of CommentPress will be working with us on the project and this will result in significant further development of CommentPress 2. So, if you’re interested in CommentPress (as many people are), please consider following, contributing to and testing JISCPress.

I should also note that while the project is a spin-off of our work on WriteToReply, neither Tony or I are personally receiving any funds from JISC. The contributions from JISC to cover our time on this project are paid directly to our employers and does not result in any financial benefit to us or WriteToReply (which is in the process of being formalised as a non-profit business). In other words, while WriteToReply is a personal project, JISCPress is part of our normal work as employees of our universities (both Tony and I are expected to bid and win project funds – you get used to it after a while!). Money has been allocated to fund dedicated developer time to the project, which will pay Eddie and Alex, a student at the University of Lincoln, for their work.

Anyway, on with the project! Here’s the outline from the bid document:

This project will deliver a demonstrator prototype publishing platform for the JISC funding call and dissemination process. It will seek to show how WordPress Multi-User (WPMU) can be used as an effective document authoring, publishing, discussion and syndication platform for JISC’s funding calls and final project reports, and demonstrate how the cumulative effect of publishing this way will lead to an improved platform for the discovery and dissemination of grant-related information and project outputs. In so doing, we hope to provide a means by which JISC project investigators can more effectively discover, and hence build on, related JISC projects. In general, the project will seek to promote openness and collaboration from the point of bid announcements onwards.

The proposed platform is inspired and informed by WriteToReply, a service developed by the principle project staff (Joss Winn and Tony Hirst) in Spring 2009 which re-publishes consultation documents for public comment and allows anyone to re-publish a document for comment by their target community. In our view, this model of publishing meets many of the intended benefits and deliverables of the Rapid Innovation call and Information Environment Programme. The project will exploit well understood and popular open source technologies to implement an alternative infrastructure that enables new processes of funding-related content creation, improves communication around funding calls and enables web-centric methods of dissemination and content re-use. The platform will be extensible and could therefore be the object of further future development by the HE developer community through the creation of plugins that provide desired functionality in the future.

My revised ALT-C proposal

I’ve just re-submitted this proposal for a demonstration at ALT-C 2009. It’s called WordPress Multi-User: BuddyPress and Beyond. It won’t be confirmed until June, but for the record, here it is…

‘BuddyPress’ is a new social networking layer for WordPress Multi-User blogs. It provides familiar, easy to use social networking features in addition to a high-quality and popular blogging platform. The University of Lincoln have been trialing WordPress MU since May 2008 and have been using BuddyPress since February 2009 to promote an institutional social networking community built around personalised and collaborative web publishing.

This session will demonstrate the versatility of the WordPress MU platform. We’ll look at an installation that is enhanced with BuddyPress, LDAP authentication, mobile phone support and advanced privacy controls. You’ll see how simple it is to set up site-wide RSS syndication and aggregation, enhance your blog with semantic web tools, publish mathematical formulae with LaTeX, send realtime notifications to Facebook, Twitter and IM, publish podcasts to iTunes, and embed GPX and KML mapping files. We’ll also look at how to embed WordPress content in your VLE and other institutional websites. The use of a temporary ‘ALT-C 2009 BuddyPress’ installation will be encouraged.

There will be opportunities throughout for questions and answers and participants will leave with a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of WordPress and the resources and skills required to provide a social networking and blogging platform in your institution.

Developing BuddyPress for education

In February, I wrote a brief post about setting up BuddyPress with LDAP authentication within a university context (you’re looking at it). Four days ago, BuddyPress reached maturity by hitting version 1.0, marking a time to reflect on what I’d like to see developed for BuddyPress for use within a university context. This is an initial wish list. I’m not looking for BuddyPress to be an all singing, all dancing, social network. I don’t care about image collections and status updates (Flickr and Twitter do those jobs nicely) I would, however, like to see it being used for building group identity (projects, special interest groups, classes, courses) and portfolio/resume building. Right now, it’s pretty limited in those areas.

Privacy controls

As I mentioned previously, our social network is private, while the blogs have five levels of optional privacy controls, ranging from public and indexed by Google, to private, single-user blogs. However, privacy within the social network is currently all or nothing. It’s a hack that works but has no flexibility. The BuddyPress activity plugin is currently turned off because the privacy plugin I use, doesn’t account for the feeds that the plugin exposes. It would be nice to be able to have the site-wide social activity visible when logged in. Currently, only information about new blog posts is published site-wide. What I would like is for everything that the activity plugin logs, to have site admin options to be 1) visible to non-logged in users/public; 2) visible to logged in users; 3) visible to my groups and friends,4) visible to my friends and 5) not visible. In addition, the feeds that are exposed of site-wide activity and member activity, could also be configurable so that 1) a site admin can choose to expose them or not; 2) if allowed, a member can choose to expose their personal feed or not; 3) a feed key could be used in place of the normal feed URI so that private member feeds could be created. Finally, groups and member profiles could optionally be made public or private. So anything following /groups/ or /members/ has an option to be visible outside the community.

Group activity

Currently, groups don’t publish very much information and you can’t aggregate information from elsewhere into a group profile. I submitted a ‘wishlist’ ticket to BuddyPress for group activity feeds, requesting that feeds for when a new group member joins and changes to the group wire. It would also be nice to be able to aggregate content from other sites via RSS into the group ‘news’ field, or a new lifestream-like field so group photos or videos or whatever, could be sucked in. It was possible to do this via a Yahoo! Pipe which combined various feeds which could then be put through feed2js and dropped into the ‘News’ field. However, embedded javascript is now intentionally blocked 🙁 I guess I could find a work-around.

Member profiles

For both teachers and students, the profile pages could be effective resumes. Currently, the site-admin can build basic grouped fields and there’s a choice of field types, too. I’d like members to be able to build their own fields and for there to be pre-built field types to choose from. It’s possible for the site admin to pre-build fields and probably easy enough for me to pre-build specific fields to design a resume (the examples given of language, country and state are just .csv lists). However, currently, if I provide three ‘Employment’ fields, a member can’t add a fourth ‘Employment’ field, nor can they select dates to correspond to when that employment was. I’m pretty sure I could create the fields, but it’s beyond me to allow a member to build their own profile pages from a selection of pre-built fields.

Finally, in addition to my request for members to be able to make their profiles public, I’d like the member profile to be marked up with hResume markup and exportable in a variety of styled formats: xhtml+css, xml, pdf, txt, doc and rtf.

The entire member profile should use microformat markup where possible. Currently, the profile can export a simple, personal hCard but could also use hCard for company and school addresses, hCalendar for dates, and rel=”tag” for creating a set of tagged skills. LinkedIn partially implements this, by the way.

So, privacy controls, group feeds and a resume builder. Not too much to ask is it? I’d probably be able to pay for the resume builder if anyone is interested…

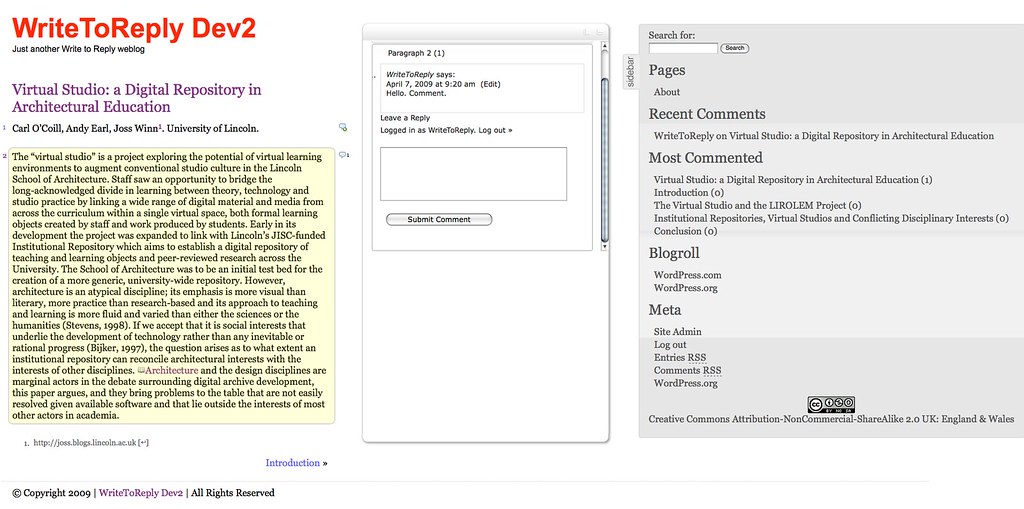

CommentPress

CommentPress is, for educators, one of the most important developments to come out of the WordPress community and one of the most significant innovations that I know of in online publishing. I first learned about it when I saw that Yale University Press were using it to invite comment on Yochai Benkler’s book, The Wealth of Networks. In its original form, CommentPress is a theme for WordPress that allows readers to comment on, annotate and discuss paragraphs of text. In fact, although installed as a theme, it transforms a site not only by design, but with functionality you’d normally expect from plugins. In CommentPress v1.x, form and function came as a single package. It’s worth reading about the background to CommentPress. You’ll see that it’s part of a larger course of research by the Institute for the Future of the Book.

Institute for the Future of the Book was founded in 2004 to [… stimulate] a broad rethinking—in publishing, academia and the world at large—of books as networked objects. CommentPress is a happy byproduct of this process, the result of a series of “networked book” experiments run by the Institute in 2006-7. The goal of these was to see whether a popular net-native publishing form, the blog, which, most would agree, is very good at covering the present moment in pithy, conversational bursts but lousy at handling larger, slow-developing works requiring more than chronological organization—whether this form might be refashioned to enable social interaction around long-form texts… We can imagine a number of possibilities: scholarly contexts: working papers, conferences, annotation projects, journals, collaborative glosses; educational: virtual classroom discussion around readings, study groups; journalism/public advocacy/networked democracy: social assessment and public dissection of government or corporate documents, cutting through opaque language and spin (like the Iraq Study Group Report, a presidential speech, the federal budget, a Walmart or Google press release); creative writing: workshopping story drafts, collaborative storytelling; recreational: social reading, book clubs.

You can also read about CommentPress in The Chronicle for Higher Education and The Journal of Electronic Publishing.

We have started to use CommentPress at the University of Lincoln for the discussion of internal documents and feedback from staff has been good. Many are astonished at what it makes possible. A departmental research strategy paper received over 100 comments from nine staff; something we’d never have had by emailing the document out for comment. Of course, I am keen to use it to support courses and a colleague and I have recently applied for funding to use CommentPress in a course with over 100 Criminology students, who are normally asked to critique texts and respond by emailing Word documents to their tutor. Using CommentPress allows for transparent and open, formative feedback and assessment by both staff and student peers.

Outside of my work for the university, I’ve been developing WriteToReply, with Tony Hirst from the Open University. You can read about how we started WriteToReply and you’ll see that CommentPress is fundamental to what we’re trying to achieve and we’re using it for networked democracy, as suggested above. CommentPress is in fact, a comment engine for each document site. Two things make this possible. First, and most obvious, is the fact that readers on a document site can direct comments to specific paragraphs of text. Readers can also respond to other readers’ comments and a happy by-product of our re-publication of the Digital Britain – Interim Report, is that the discussion still continues, despite the consultation period being over. So CommentPress is an engine for on-site comment and discussion. Texts are dissected but remain whole; they also become social objects.

The second important contribution CommentPress has made is the provision of permalinks for each paragraph in the text. This provides a unique URI or URL for each paragraph of text, making linked references from third-party web sites possible. Combined with the trackback/pingback system built into decent web publishing platforms, CommentPress makes remote commenting on text possible, as Tony explains on his blog.

What this means is that the paragraph, action point, section or whatever can become a linked resource, or linked context, and can support remote commenting. And in turn, the remark made on the third party site can become a linked annotation to the corresponding part of the original report… How? Well through the judicious use of trackbacks… So even if you don’t want to comment on the Digital Britain Interim report on the WriteToReply site, but you do care, why not post your thoughts on your own blog, and link your thoughts directly back to the appropriate part of the report on WriteToReply?

It’s this feature, so easily missed, which makes CommentPress a comment engine. An engine suggests an underlying technology that drives something greater. By introducing paragraph permalinks, text can now be linked at a much more accurate and deeper level than was previous possible. Texts are transformed into uniquely identifiable resources of data. Academics can now reference paragraphs rather than page numbers and readers can reflect, comment and participate in the analysis of texts from their own site. For the reader, CommentPress provides a fluid interface to the document as a whole but at a technical level, explodes it across the Internet.

In the running of WriteToReply, we’ve tested CommentPress quite hard and found it to be a complex and fragile tool. Until recently, it hasn’t been updated to reflect the fast changing development of WordPress and because of its extensive use of Javascript, it clashes with other plugins, so while it transforms a WordPress site, it also restricts functionality otherwise possible. Fortunately, CommentPress 2 is being actively worked on and I’ve been helping to test it with Eddie Tejeda, the original developer. It’s currently in beta, but Eddie is responding to my feedback and fixing issues rapidly. There is a mailing list for CommentPress and the code is publicly accessible.

If you test CommentPress 2, you’ll immediately see that it’s been split into a suite of plugins and themes and that it’s now much more flexible in terms of compatibility with other WordPress plugins and in being able to select different components, options and themes. Notably, paragraph permalinks are available as a separate plugin, which means that any WordPress blog will be able to have paragraph-level URIs, without necessarily supporting paragraph level commenting. My test site is on WriteToReply. Feel free to have a look and post comments, if you wish. As I write, it’s not quite ready for everyday use, but at the speed which Eddie has been working over the last few days, I’m confident that I’ll be able to use it here at the university and on WriteToReply before the month’s out. If you’re used to using v1.4.1, you’ll notice a lot of change. Remember that it’s still beta software and that not all of the features have been fully implemented yet. It would be great if other people could help test it across various browsers and with different documents. Multimedia is not something I’ve yet been able to throw at it, for example.

Finally, CommentPress needs continued support in terms of testing, reporting issues, bug fxes and feature development. This can be done voluntarily, but given it’s potential to support education, business and government consultations, I for one, will be looking for ways to raise funding to help support all of this. If you know of any possible funding opportunities within UK Higher Education, please do let me know.

How the world has changed…

“When I learned electronics, we soldered together discrete components to make a product. Today, we combine copyrighted units of other people’s intellectual property to make a product. And we don’t really have the tools to carry out that task properly.”

A comment by Bruce Perens, the creator of the Open Source Definition, the manifesto of Open Source and the criterion for Open Source software licensing. Perens represented Open Source at the United Nations World Summit on the Information Society, at the request of the United Nations Development Program.