I offer this as one response to my previous post. Much more needs to be done to ‘reverse imagineer’ EdTech, but this will be my practical focus for the foreseeable future and the nexus of where theory is put into practice, where pedagogy meets technología: “The processes and practices of doing things, understanding things and developing knowledge”? (Selwyn 2011, p7)

A new group

In January, I wrote about how I had written a paper for the university about the role of technology in the context of Student as Producer. The paper included a recommendation that a new team be convened to “further the research, development and support of technology” at the university. January feels like a long time ago now, and I wanted to write about what’s been happening since then, because it’s all good 🙂

Following my presentation of the original paper to the Teaching and Learning Committee, I was asked to provide more detail on what the proposed team would do and a justification for the budget I had outlined. Both papers were written on behalf of and with the co-operation of, the Dean of Teaching and Learning, the University Librarian, the Prof. of Education, the Head of ICT and the Vice President of Academic Affairs in the Student Union. The second paper went back to the T&L Committee and, following their approval, then went to the university’s Executive Board in early April.

I began the paper by outlining what the team is for:

The team will consolidate and extend the existing collaborative work taking place between Centre for Educational Research and Development, The Library and ICT Services ((Since writing this, I’ve listed examples of our existing work in a recent blog post. You can add JISCPress and ChemistryFM, this WordPress platform and our e-portfolio system to that list, too.)) and invite staff and students from across the university to join the team. The team will offer incentives to staff and students who wish to contribute to the rapid innovation of appropriate technology for education at the university, through work-experience, research bursaries and internal and external applications for funding. Through our experience of the Fund for Educational Development (FED) and Undergraduate Research Opportunity Scheme (UROS) funds, we know this is an effective method of engaging staff and students in research and development. A core principle of the team will be that students and staff have much to learn from each other and that students as producers can be agents of change in the use of technology for education.

I then went on to argue:

The Student as Producer project is anticipated to take between 3-5 years to fully embed across the university. During this time, significant changes will occur in the technologies we use. In just the last five years, we have seen the rise of web applications such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Web 2.0 in general. Aside from such applications, networked infrastructure has developed considerably, with access to broadband now widespread and the use of smart phones and netbooks rapidly increasing. For a student at the University of Lincoln in 2011, high-speed networks are now ubiquitous across the city campuses and such networks themselves are now the ‘learning landscape’, in which the university is but one part.

There is a strong argument for shifting away from the idea of ‘educational technology’ to address technology straight on, recognising that any technology can support and enhance the research, teaching and learning process, and that the use of these technologies increasingly lies outside the institution’s control. We would argue that it is not the university’s role to compete with or determine the use of any technology but rather support access to technology in the broadest terms. This can be achieved through incremental improvements to infrastructure (e.g. network capacity and ease of use), supporting staff and students (e.g. training, workshops, courses) and personalising and integrating the services we do provide so that staff and students have a useful and enjoyable experience of technology at the university and understand how it fits within their wider networks. In particular, we should consider whether Blackboard can be better enhanced through mobile applications and the integration of other popular services such as Facebook. It is a key technology for the support of teaching and learning and if extended through the work of the proposed team, could be a platform for innovation. All of this work should be informed by a broad understanding of the social roles of technology and the objective of producing critical, digitally literate staff and students.

I presented a list of risks that I thought would present themselves if we didn’t take this approach:

- Poor co-ordination: Poorly co-ordinated investment in technology to support strategic objectives, resulting in competing interests in limited resources.

- Disjuncture: Growing disjuncture between student expectations and institutional provision of technology and support.

- Inertia: No locus for technological experimentation and innovation.

- Unattractive to potential post-graduates and staff: Technological provision compares poorly to other institutions, putting off new staff and post-graduates.

- Loss of income stream: Under-investment in ‘seeding’ projects that may attract external income.

- Business As Usual: During a period of significant change in Higher Education, our progressive T&L Strategy is hindered by poorly co-ordinated technological development.

- Student as Consumer: Technology remains something ‘provided’ by the university, rather than produced and informed by its staff and students.

Finally, I provided more detail about the costs. After taking into account existing budgets available to us and anticipated external research income, the total I asked for was £22K/yr to pay for an additional 12-month Intern position and a contribution to the staff and student bursaries we want to make available. This was approved.

I was pleased with the outcome as it means that our current work is being recognised as well as the strategic direction we wish to go in. In terms of resourcing, we will have at least one more full-time (Intern) post and hold a £20K annual budget which will be used to provide grants and bursaries to staff and students, pay for hardware and software as needed and pay for participants to go to conferences to discuss their work and learn from the EdTech community at large. This doesn’t include any external income that we hope to generate. The nature of our applications for research grants is unlikely to change other than we hope to have more capacity in the future including both students and academic staff as active contributors to the development, implementation and support of technology for education at the university.

Team? Group? Network? Place?

The core members of the group (i.e. CERD/ICT/Library) met for an afternoon last week to discuss the roadmap for getting everything in place for the new academic year. We began by discussing the remit of the group (as detailed in the two committee papers), which is principally to serve the objectives of Student as Producer, the de facto teaching and learning strategy of the university. We spent a while discussing the nature of the group; that is, whether it was a team, a network, a group or even a place. In the first committee paper I wrote, I described it as “a flexible, cross-departmental team of staff and student peers”, but have since come to refer to it as a ‘group’, as ‘team’ does not reflect the nature of how we intend to work, nor the relationships we hope to build among participants, nor is a ‘team’ inclusive enough. I’d like to think that we’ll develop a network of interested staff and students and even attract interest and collaboration from outside the university, but I think it’s too early to call what we’re doing a network, although we are networked and working on the Net. We’ve given ourselves a couple of weeks to come up with name but whatever we call it, we agreed that in principle we’d govern the group by consensus among us. Ideally, though not always in practice, the Net can help us create flatter structures of governance, so we’ll try to shape the way we work around this ideal. My role will be to co-ordinate the work of the group by consensus.

UPDATE: We decided upon LNCD as the name for our group. It’s a recursive acronym: LNCD’s Not a Central Development group.

All participants will be encouraged to write about their work in the context of Student as Producer, building on the progressive pedagogical framework that is being implemented at the university, theorising their work critically and reflexively. We’ll support this approach, too, building a reading list for people wanting to think critically about EdTech and an occasional seminar series where we’ll discuss our ideas critically, reflexively and collegially.

Road map and tools

We will be up and running by the start of the next academic year. Over the summer, we’ve got a timetable of work that we plan to do to ensure we’ve got a clearly defined identity and the tools in place to support the nature of our work. By the end of September, we’ll have a website that offers clear information on what we do, what we’re working on, how to get involved and the ways we can support staff and students at the university. The site will allow you to review all aspects of our projects as well as propose new projects which can be voted up and down according to staff and students’ priority. There will be an application form for you to apply for funding from us and a number of ways for you discuss your ideas on and offline. We’ll be continuing our current provision of staff training, but will be looking to re-develop the sessions into short courses that are useful to both staff and students. The 2009 Higher Education in a Web 2.0 World report recommended that

The time would seem to be right seriously and systematically to begin the process of renegotiating the relationship between tutor and student to bring about a situation where each recognises and values the other’s expertise and capability and works together to capitalise on it. This implies drawing students into the development of approaches to teaching and learning. [Higher Education in a Web 2.0 World, p.9]

This is very much what Student as Producer is aiming to do through embedding research-engaged teaching and learning across the curricula and the approach we plan to take around support and training for the use of technology in teaching and learning. We’ll be working with the Student Union and the Principle Teacher Fellows across the university to identify ways that students and their tutors can be encouraged to support each other and we welcome the input and collaboration of anyone who wishes to adopt and advocate this approach. We’ll be designing some posters, flyers and business cards over the summer so that people around the university know who we are and how to get in touch in time for Fresher’s Week.

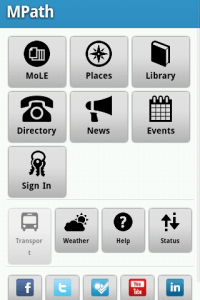

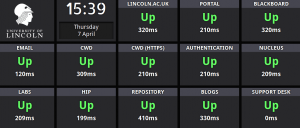

For the Geeks, you might be interested to know that we’ve decided upon a set of tools for managing our work online in a distributed environment where most of us work in different parts of the university campuses. We’ll have a dedicated virtual Linux box (as well as our usual development servers) and the main website will be run on WordPress using our own custom CWD theme. We’ll be migrating all of our code to Git Hub very soon and we’ll be using Pivotal Tracker to manage our development tasks in an agile and open way. We’ll be using our existing combination of Get Satisfaction and Zen Desk to manage peer-to-peer user support and bug reports and we’ll also be looking at alternatives such as User Voice and the Open Source Q&A tool to provide a way for you to suggest and vote for project ideas. Notably, through the use of their APIs, most of these tools integrate well, so that we can create tasks in Pivotal Tracker from bug reports made with Zen Desk and associate those tasks with commits on Git Hub. We’ll be using Twitter just as we always do, and we’ll be using Google Groups for longer discussions around each project (as well as regularly meeting face-to-face, of course). For projects that don’t involve writing code (which we certainly welcome), we’ll be looking at tools that assist with resource development and document control, such as digress.it, MediaWiki, Git Hub, Google Docs, EPrints and Jorum, depending on the nature of the project. We won’t be prescriptive with the tools we adopt, using whatever is appropriate, but with an emphasis on those that offer decent APIs, data portability and good usability. Proprietary software lacking APIs and with poor usability (we can all think of a few) won’t get much of a look in. Finally, through RSS and widgets, we’ll be presenting a coherent picture of each project on the main website.

There’s quite a bit to do but we know how to do it. If you’ve got any suggestions (a name would be useful!), ideas or even want to join us, for the time-being, leave a comment here and we’ll get back to you. Thanks.