Tony Hirst recently blogged about the Open Data scene in UK HE, mentioning Lincoln as one of the few universities that are currently contributing HEI-related #opendata to the web. Sooner or later, I’ll write a more reflective post, but here I just wanted to document the current situation (that I’m aware of) at Lincoln. There are two groups that take an interest in furthering open data at Lincoln: LiSC, led by Prof. Shaun Lawson, and LNCD, the new cross-university group I co-ordinate which consolidates a lot of the previous and current work listed below. (For a broader overview of recent work, see this post).

Derek Foster in LiSC recently released energy data from our main campus buildings, updated every 2hrs on Pachube. I was just speaking to Nick and Alex and I think they plan to pull this data into our nucleus datastore, combine it with the campus location-based work we’ve done and generate dynamic heat maps (assuming Derek isn’t already working on something similar??)

LiSC are also mashing open data from the UK Police Crime Statistics database to create a social application called FearSquare and last week put together MashMyGov, a site that randomly suggests mashups using data sourced from Data.Gov.UK.

In the past couple of years, LNCD have worked on:

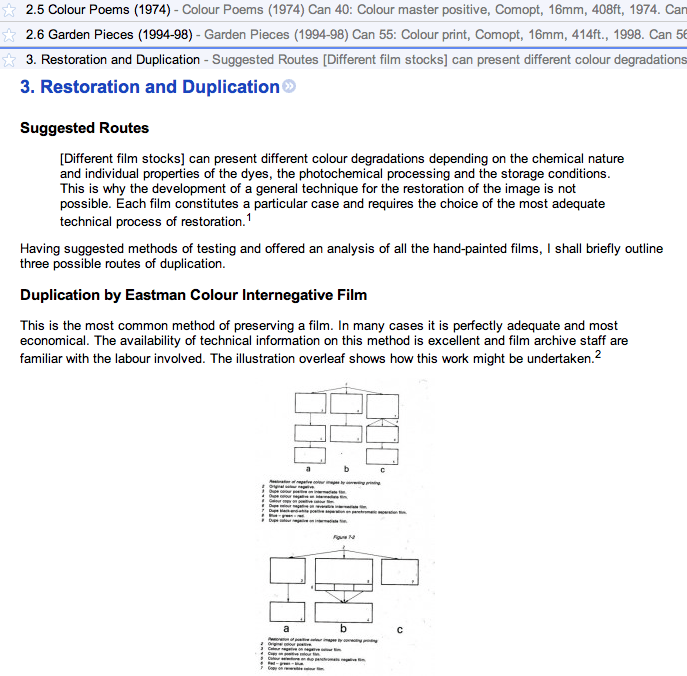

JISCPress, a 2009/10 project we worked on that didn’t release any data but developed a prototype WordPress platform that atomises documents for publication and comment on the web and spits out lots of data in open formats. It also uses OpenCalais, Triplify and can push RDF Linked Data to the Talis Platform. JISC now use it to publish documents for comment.

Total Recal, a JISC-funded project we completed recently and will roll out across the university this September. As well as providing a fairly comprehensive and flexible calendaring service at the university, it allowed us to work on our space-time data and develop a number of APIs on top of…

Nucleus, the epicentre of our open data efforts. This is a data store, using MongoDB, which aggregates data from a number of disparate university databases and makes that data available over secure APIs. Through a lot of hard work over the last year, Alex and Nick have compiled the single largest data store that we have at the university. Currently, it offers APIs to university events, calendars, locations and people. We’ll also be adding APIs to over 250,000 CC0 licensed bibliographic records held in Nucleus, too (see Jerome below). It also uses the OAuth-based authentication that Alex has developed.

Linking You, is a JISC-funded project we delivered last week to JISC, which looked at our use of URIs, undertook a comparative study of 40 HEI websites (more to come), proposed a high-level data model for use by the HEI sector and made some recommendations for further work. What we’ve learned on this project will have a lasting effect on the way we present our data and on our wider advocacy of open data to the university sector. I really hope that our recommendations will lead us to more discussion and collaboration with people interested in opening university data.

lncn.eu, a URL shortener that Alex and Nick developed in their spare time for a while and has since been formally adopted by the university. Naturally, lncn.eu has an API and can be used (e.g. Jerome) as a proxy for other services, collecting real-time analytics.

Jerome, is a current JISC-funded project that will release over 250,000 bibliographic records under a CC0 license. The data is stored in Nucleus and documented APIs will be available by the end of July. This is a very cool project managed by Paul Stainthorp in the Library (who’s also a member of LNCD).

We’re currently using data.online.lincoln.ac.uk to document the data that is accessible over our APIs. At some point, I can see us moving to data.lincoln.ac.uk – we just need to find time to discuss this with the right people. So far, we haven’t really gone down the RDF/Linked Data route, preferring to offer data that is linked (e.g. locations and events data are linked) and publicly accessible over APIs that are authenticated where necessary and open whenever possible. We are keen to engage in the RDF/Linked Data discussion – it’s just a matter of finding time. Please invite us to your discussions, if you think we might have something to contribute!