What impact might the increasing cost of energy have on Higher Education? My interest is not simply about the impact on institutional spending, but rather the deeper and broader socio-economic effects that an energy crisis might have on the provision of Higher Education. To the extent that Universities are businesses, I am interested in ‘business continuity’, but equally I am interested in whether the current energy intensive model of HE will remain viable and whether an energy crisis might act as a catalyst to changes in the nature of Higher Education within society.

This forms part of an on-going series of blog posts/essays, which are being collected under the tag #resilienteducation (RSS feed). My thinking on these issues is by no means complete or even coherent at times but through sketching out these ideas and hopefully receiving feedback, we can all offer useful observations on and possible solutions for the future of Higher Education. You will see that Richard Hall has recently begun to address this too, questioning the relevancy of curricula, and how building resilience to the related impacts of an energy crisis and climate change might inform learning design and pedagogy.

I appreciate that a discussion about energy fundamentals is not part of the usual discourse around educational provision, but my proposal is that it should be and will be, just as there is already a discourse around the increasing role of educational technology, which is, from one point of view, merely leveraging affordable and abundant energy for the purposes of research, teaching and learning.

In fact, the discourse around energy has already begun under the guise of Climate Change and Sustainability. When we speak of sustainability with regards to Climate Change, we are referring to a transition from a society built on fossil-fuel energy to one that is not. If adhered to, this compelling transition will be more profound than anything we have experienced in our lifetimes and is likely to last our entire professional lives, too.

As the crucial issue of Climate Change begins to dominate all aspects of society, so I expect an interest in the fundamentals of energy policy, security, production and consumption to surface in discussions about the nature of our institutional provision of education, just as an interest in carbon emissions and sustainability is surfacing now.

The facts

During the period of 2007-8, GDP in the UK hovered somewhere between 2-3%:

Looking at the Consumer Price Index (CPI) between 2007-8, inflation rose from about 2% to 5%:

Individual earnings increased, on average, just under 4% each year during 2007-8:

Average household income in 2007-8 was about £30K:

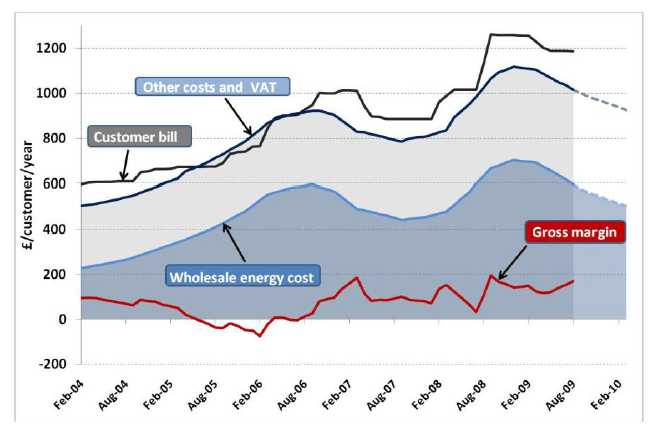

Now, moving on to energy, consumer ‘dual fuel’ bills have more than doubled since 2004.

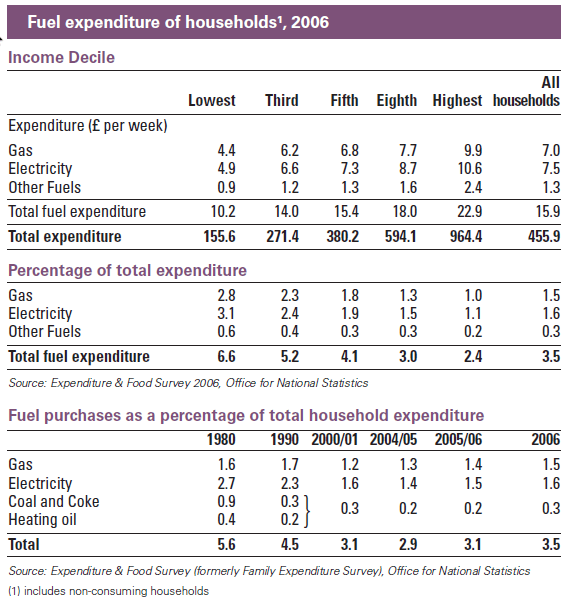

In 2006 (the latest figures I can find), household fuels made up, on average, 3.5% of household income. Though bear in mind that this is an average. For lower income households, it rose to 6.6%.

With the average household final income at just under £30K and the average annual household duel fuel bill at over £1200, the current percentage expenditure on household energy is more like 4%.

The scenario

In October this year, Ofgem forecast that UK domestic energy bills could rise by up to 60% over the next ten years in a scenario where the economy recovered and there is a competitive ‘dash for energy’ between countries for energy resources. Specifically, they see a difficult period around 2016 due to the closure of domestic facilities and an increased reliance on imported fuels. ((For a good overview of energy security in the EU, see the recent Briefing Paper from Chatham House: Europe’s Energy Security After Copenhagen: Time for a Retrofit?)) However, last week, at a House of Commons Select Committee, Alistair Buchanan, the chief executive of Ofgem, said that following more recent discussions with energy suppliers and academics, the 60% figure is now seen as too optimistic. He didn’t offer a revised figure from 60%, but we might consider research by Ernst & Young (commissioned by uSwitch), that warns of up to a 400% increase in the costs of domestic fuel by 2020. That is, average annual domestic energy bills could increase from £1243/year to £4733/year. ((Household fuel bills to hit almost £5K in ten years time (PDF) )) This doesn’t mean very much until we compare it to increases in average household income which, looking at the individual income, GDP and inflation charts above, we might optimistically suggest will climb back to about 3-4% each year. The forecast isn’t quite as good as that in the medium term though, with GDP predicted to grow by 1.1% in 2010, 2% in 2011, 2.3% in 2012 and 2.7% in 2013. Inflation (CPI) is likewise forecast at 1.9%, 1.6%, 2% and 2.3% each year, respectively. Anyway, let’s be a bit optimistic and say that the average final household income will rise from about £29K to around £37K in 2020 (about +2.5%/year – my Union has just agreed to a 0.5% pay increase this year). The percentage of household income spent on the £4733 energy bill would rise from 4% to nearly 13% in 2020. That’s a significant chunk of household income that for many people would force ‘efficiencies’ in energy use, result in cuts in other household spending and contribute to further fuel poverty. In terms of the Jevons Paradox, it may be understood as a method of controlling the energy consumption of the average household.

The bigger picture

It’s useful to look at the bigger energy picture presented in my last post and consider the effect that the price of oil had on energy prices, inflation and GDP during the last few years. The prices of gas and electricity correlate closely to the price of oil:

Of course, not only does the price of electricity rise with oil, but the price of fuels for transportation rise, too, and when transportation costs rise, everything else, including food and consumer goods, rise. ((For 2008 average fuel prices, see The AA’s Fuel Prices 2008)) Look back to the inflation chart above and see how inflation peaked above 5% in September 2008 not long after the price of oil peaked at $147/barrel in July 2008. The effect is, unsurprisingly, that as living gets more expensive and results in sustained debts we cannot manage, we are forced to curtail consumption and GDP slows. I mentioned in my last post that there is a belief that oil price spikes lead to recessions. ((See James Hamilton’s paper, ‘Causes and Consequences of the Oil Shock of 2007-08’. It’s worth starting from a discussion on The Oil Drum, where you can download the paper. For a more succinct summary, see the FT article here and a rebuke here. Still, even the rebuke recognises the impact oil can have on an economy: “It is through second-round effects that inflation can rise. For an oil importer, a rise in the price of oil means that the country is poorer as a whole. No matter what policy action they take, their terms of trade have deteriorated.”))

Look again at the chart below, which I used in my previous post and shows the price of oil over the last few years with a projection to 2012. The forecast of oil at around $175/barrel within the next two years, based on what we’ve just seen above, suggests the possibility of a sustained recession as economic growth is limited by the availability of affordable energy. Given the recent volatility of the oil market, we should be cautious of forecasting prices, but can, with more confidence, predict supply and demand, which prices are linked to. With oil production at a plateau, “chronic under-investment” in the oil industry (despite record income) and the additional price of carbon added to energy consumption, the retail price of energy to consumers is unlikely to go against the trend shown in this graph. Other sources confirm the likelihood of an ‘oil crunch’ before 2015. For example, see the interview with the IEA’s Chief Economist and a report from Chatham House, which warns of a crunch by 2013 and the possibility of prices topping $200 per barrel.

Finally, there is a whole other local issue of declining revenues from North Sea Oil, which was presented as a grave problem to the All Party Parliamentary Group on Oil and Gas, this week. If this post interests you, I highly recommend spending 30 minutes reading this paper which accompanied the presentation and discusses these issues in much greater depth and breadth. The paper concludes:

If we look forward, taking into account the biophysical restrictions, a major change in the nature of our economy is certain – if only because the reality of our situation dictates that it can’t stay the same. That is the political issue that British society must reconcile itself to. For the last two decades we have been living a lifestyle that has been sustained by the wealth and power created by indigenous energy resources. That cannot continue, and the process of moving from an economy that has no limits to one that must operate within more tightly constrained limits is going to be a difficult re-adjustment for many: For the political class it means redefining what it is society represents, and what its aspirations should be; for the business community it means redefining what the term “business as usual” really means; and for the public it means reassessing their own material aspirations, and perhaps a return to a far less energetic lifestyle that in terms of energy and material consumption is likely to be similar to the levels which existed in the 1950s or 1960s.

Perhaps at a later date, we might look at Higher Education in the 1950s and 60s in some detail…?

Universities are large consumers of energy

If oil and therefore energy prices are to continue to rise as both the chart above and the uSwitch research warns, what might be the cost to Higher Education? A 2008 paper estimated that UK Higher Education Institutions spent around £300m on energy in 2006, an increase of 0.5% since 2001 and representing 1.6% of total income. ((Ian Ward, Anthony Ogbonna, Hasim Altan, Sector review of UK higher education energy consumption, Energy Policy, Volume 36, Issue 8, August 2008, Pages 2939-2949, ISSN 0301-4215, DOI: 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.03.031.))

This review reveals that the energy consumption levels in UK HEIs increased by about 2.7% over the 6-year period between 2001 and 2006. The building energy-related CO2 emissions are estimated to have increased by approximately 4.3% between 2005 and 2006 alone. These trends run contrary to the national plans for emissions reductions in all sectors and are therefore a cause for action.

The Sustainable ICT project estimated that around £60m of the £300m (1/5th) was to power ICT. ((Sustainable ICT in Further and Higher Education: SusteIT Final Report, p. 97)) Since 2006, energy bills have risen by about 25% so we might expect HEIs annual electricity costs to currently be around £375m, with ICT use around £75m. The increase in the number of students in Higher Education has not resulted in a corresponding increase in energy use; closer correlations can be found between floor space and energy use and, interestingly, between research activity and energy consumption. The more research intensive universities use relatively more energy. ((Ian Ward, Anthony Ogbonna, Hasim Altan, Sector review of UK higher education energy consumption, Energy Policy, Volume 36, Issue 8, August 2008, Pages 2939-2949, ISSN 0301-4215, DOI: 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.03.031. Another interesting figure that the paper observes is that the ‘downstream’ energy use for the sector, which includes suppliers, business and student travel represents 1.5 times the direct energy consumption of the sector.)) But enough about energy prices. Annual income of HEIs increased by 10% to £23.4bn between 2007-8 and total expenditure likewise increased by 9%. ((HESA: Sources of income for UK HEIs 2006/07 and 2007/08)) How would an energy shock of +400% , increasing sector-wide energy costs from £375m to £1.5bn over the next ten years, be managed when income and spending appear to be so tightly coupled? On a more local level, my institution’s gas, electricity and oil bill is forecast to be £1.63m in 2009/10, up 6% on the last year. What would be the impact on us of an annual bill of £6.5m in 2020? (In 2007, our university had a budget surplus of £2.6m). ((University of Lincoln Financial Statements)) What areas of income are likely to accommodate an increased spend of up to 400% in ten years? Efficiencies in energy use can help, but even with planned cuts in consumption of around 5% next year, the annual cost of electricity, gas and oil at this university is still expected to rise by 0.8% under current energy prices.

Sustainability or resilience?

Resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganise while undergoing change, so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity and feedbacks. ((Although it requires more elaboration and consideration in terms of educational provision, this is the common definition of ‘resilience’ used by the Transition Town movement adopted from Brian Walker and David Salt, (2006) Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. See Rob Hopkins (2008) The Transition Handbook. From oil dependency to local resilience. For an academic critique of the Transition Town’s use of ‘resilience’, see Alex Haxeltine and Gill Seyfang, ‘Transitions for the People: Theory and Practice of ‘Transition’ and ‘Resilience’ in the UK’s Transition Movement’. A paper presented at the 1st European Conference on Sustainability Transitions, July 2009))

What actions can HEIs take to be resilient and therefore remain relevant as dramatic social changes occur in our use of energy and therefore material consumption and output?

Resilience, it seems to me, is a pre-requisite for sustainability if you accept the tangible and coupled threats of energy security and climate change enforcing long-term zero or negative growth. If oil production has peaked just prior to the worst economic crisis in living memory and faced with the need to reduce carbon emissions by at least 80% in the next forty years, should we not first develop a more resilient model that we wish to sustain?

In terms of energy use, can efficiencies lead to sustainability? At what point does ‘efficiency’ actually mean conservation and rationing? At what point do we change our habits, our practices, our institutions instead of telling ourselves that we are being efficient, as we do today? How can we teach a relevant curricula with less money (due to funding cuts and higher costs) and less energy?

To what extent is Higher Education coupled to economic growth? Universities contribute 2.3% of UK GDP but to what extent are universities dependent on economic growth? How would a university operate under a stable but zero growth economy? To what extent is educational participation dependent on economic growth?

Sorry, lots of questions but fewer answers right now.

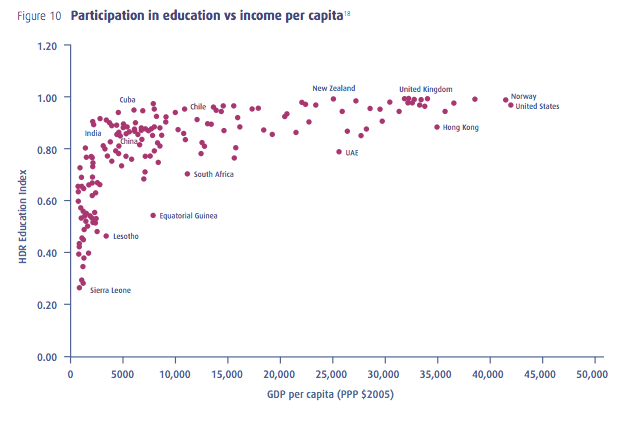

The Sustainable Development Commission, “the Government’s independent watchdog on sustainable development”, published a report earlier this year called Prosperity without Growth, the transition to a sustainable economy. The publication (recently developed into a book), examines what ‘prosperity’ means and discussed education alongside other ‘basic entitlements’ such as health and employment. In particular, the author argues that these basic entitlements need not intrinsically be coupled with growth. He argues that growth itself is unsustainable and that high standards of health, education, life expectancy, etc. are not coupled with higher levels of income everywhere.

Interestingly, there is no hard and fast rule here on the relationship between income growth and improved flourishing. The poorest countries certainly suffer extraordinary deprivations in life expectancy, infant mortality and educational participation. But as incomes grow beyond about $15,000 per capita the returns to growth diminish substantially. Some countries achieve remarkable levels of flourishing with only a fraction of the income available to richer nations. [p. 43]

Chapter four of the publication includes a useful discussion on economic growth, technological efficiency and resilience concluding:

…the answer to the question of whether growth is functional for stability is this: in a growth-based economy, growth is functional for stability. The capitalist model has no easy route to a steady-state position. Its natural dynamics push it towards one of two states: expansion or collapse.

Put in its simplest form the ‘dilemma of growth’ can now be stated in terms of two propositions:

- Growth is unsustainable – at least in its current form. Burgeoning resource consumption and rising environmental costs are compounding profound disparities in social wellbeing

- ‘De-growth’ is unstable – at least under present conditions. Declining consumer demand leads to rising unemployment, falling competitiveness and a spiral of recession.

This dilemma looks at first like an impossibility theorem for a lasting prosperity. But it cannot be avoided and has to be taken seriously. The failure to do so is the single biggest threat to sustainability that we face.

Decoupling participation in Higher Education from energy use and emissions

We can see from the chart above that Cuban citizens enjoy roughly the same level of educational participation as the UK, yet their GDP per capita is just a quarter of that of the UK. Participation in this case, is “the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrolment ratio.” ((What is the Human Development Index?)) Cuba’s energy use per capita is also just a quarter of the UK’s consumption, suggesting that while GDP and energy consumption are closely coupled, GDP and educational participation need not be.

In terms of UK HEI’s resilience, how can opportunities for participation in Higher Education remain widespread in a low energy, zero growth scenario? The Sector review of UK higher education energy consumption showed that energy consumption is not tightly coupled with student numbers, although close correlations between floor space, the number of research students and FTE staff can be seen. Does that mean that the smaller, less research intensive universities are better placed than the larger, research intensive institutions in an energy crisis scenario? Is a model of fewer universities with a higher staff-to-student ratio the answer? What other attributes, other than floor space and research activity could be used to measure resilience against the economic impact of an energy crisis?

Again, lots of questions, but fewer answers right now. Have you got any?