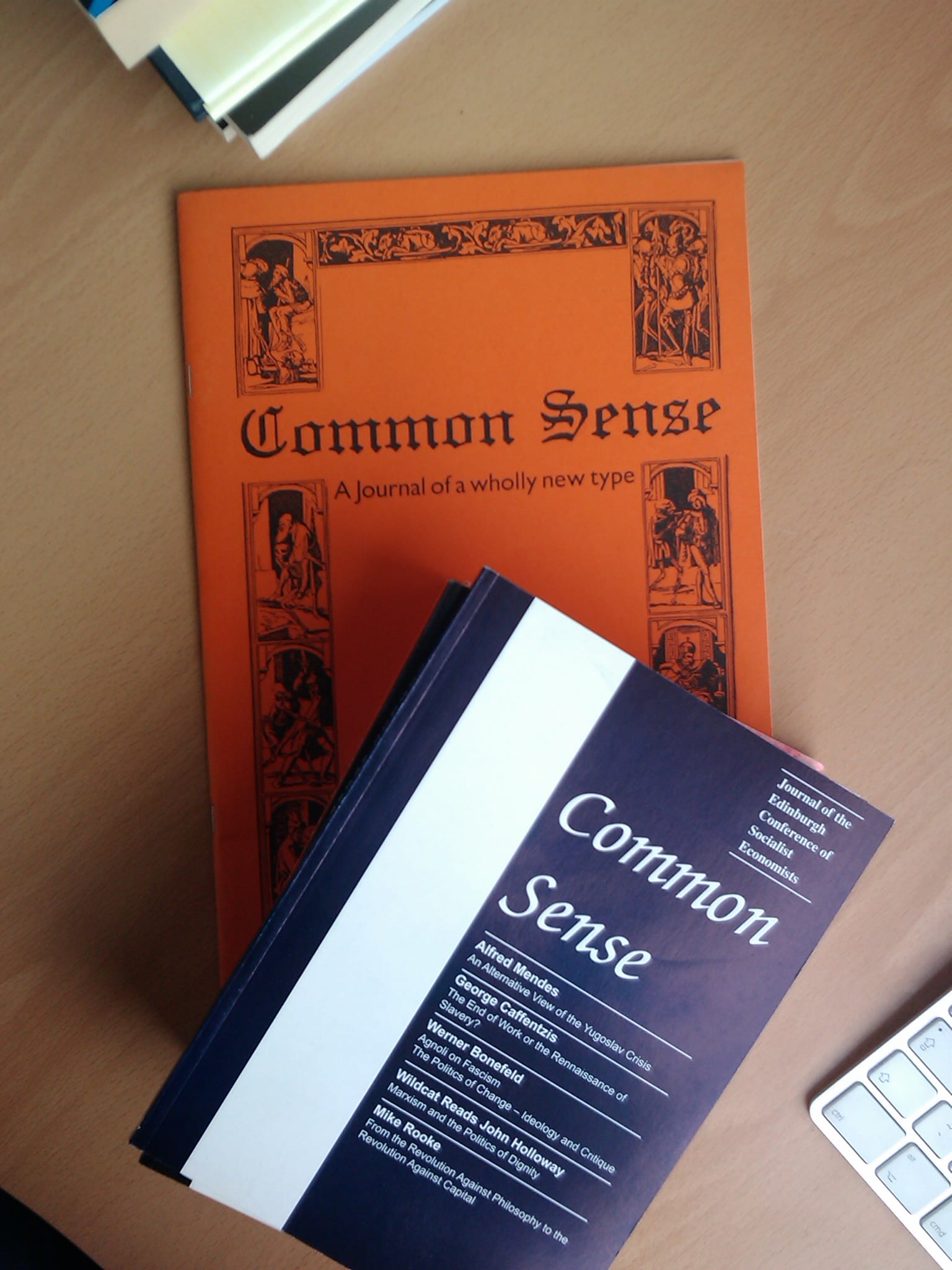

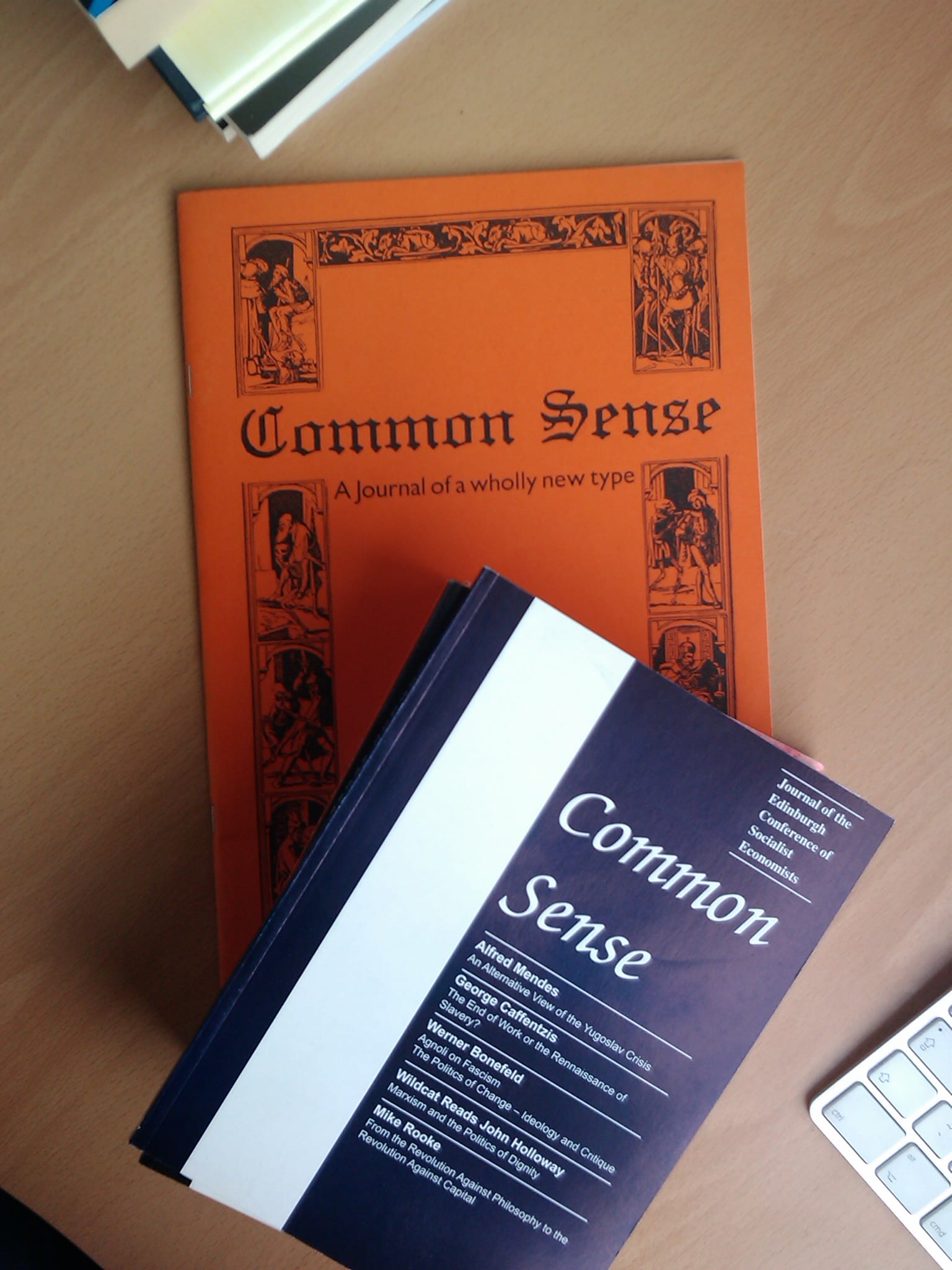

Last week, I wrote to Werner Bonefeld, seeking a couple of articles that were published in Common Sense. Journal of the Edinburgh Conference of Socialist Economists. This journal is pretty hard to come by these days. Back-issues are limited and relatively few of the articles exist on the web. It was published from 1987 to 1999, over 24 issues of about 100 pages each. As you can see from the image, early issues (one to nine) look more like an A4, photocopied zine than an academic journal, but later issues take the more traditional form and were distributed by AK Press. A few articles were collected and published in 2003.

Last week, I wrote to Werner Bonefeld, seeking a couple of articles that were published in Common Sense. Journal of the Edinburgh Conference of Socialist Economists. This journal is pretty hard to come by these days. Back-issues are limited and relatively few of the articles exist on the web. It was published from 1987 to 1999, over 24 issues of about 100 pages each. As you can see from the image, early issues (one to nine) look more like an A4, photocopied zine than an academic journal, but later issues take the more traditional form and were distributed by AK Press. A few articles were collected and published in 2003.

In my email to Werner, I mentioned that if I could get my hands on whole issues of the journal, I would digitise them for distribution on the web. As an editor of the journal, Werner was grateful and said that copyright was not a problem. I didn’t realised that Werner would send quite so many issues of the journal, but yesterday 15 of the 24 issues of Common Sense arrived in the post, along with a copy of his recent book, Subverting the Present, Imagining the Future.

My plan is to create high quality digital, searchable, versions of every issue of Common Sense over the next few months and offer them to Werner for his website, or I can create a website for them myself. I’ve done a lot of image digitisation over the years but not text. If you have some useful advice for me, please leave a comment here. I’ll also seek advice from the Librarians here, who have experience digitising books.

I have issues 10 to 24 (though not 11) and issue five. To begin my hunt for missing copies, I’ve ordered issues 1,2 & 3 from the British Library’s Interlibrary Loan service. An email this morning told me that the BL don’t have copies of the journal and are hunting them down from other libraries. We’ll see what they come up with. If you have issues 1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9 or eleven, I’d be grateful if you’d get in touch. It would be good to digitise the full set and I’ll return any copies that I’m sent.

Why go to all this trouble?

Well, Common Sense was an important and influential journal “of and for social revolutionary theory and practice, ideas and politics.” In issue 21, reflecting on ten years of Common Sense, the editorial stated that:

Our project is class analysis and we aim to provide a platform for critical debates unfettered by conventional fragmentations of knowledge (either into ‘fields’ of knowledge or ‘types’ of knowledge, e.g. ‘academic’ and ‘non-academic’). This continuity in the concepts of class struggle and social change flies in the face of most interpretations of the last 10 years.

When the journal switched from A4 to A5 size, in May 1991 with issue ten, the editorial collective reflected on the first few years of the journal.

Common Sense was first produced in Edinburgh in 1987. It offered a direct challenge to the theory production machines of specialised academic journals, and tried to move the articulation of intellectual work beyond the collapsing discipline of the universities. It was organised according to minimalist production and editorial process which received contributions that could be photocopied and stapled together. It was reproduced in small numbers, distributed to friends, and sold at cost price in local bookshops and in a few outposts throughout the world. It maintained three interrelated commitments: to provide an open space wherein discussion could take place without regard to style or to the rigid classification of material into predefined subject areas; to articulate critical positions within the contemporary political climate; and to animate the hidden Scottish passion for general ideas. Within the context of the time, the formative impetus of Common Sense was a desire to juxtapose disparate work and to provide a continuously open space for a general critique of the societies in which we live.

The change in form that occurred with issue ten was a conscious decision to overcome the “restrictive” aspects of the minimalist attitude to production that had governed issues 1 to 9, which were filled with work by ranters, poets, philosophers, theorists, musicians, cartoonists, artists, students, teachers, writers and “whosoever could produce work that could be photocopied.” However, the change in form did not mark a conscious change in content for the journal, and the basic commitment “to pose the question of what the common sense of our age is, to articulate critical positions in the present, and to offer a space for those who have produced work that they feel should be disseminated but that would never be sanctioned by the dubious forces of the intellectual police.” Further in the editorial of issue ten, they write:

The producers of Common Sense remain committed to the journal’s original brief – to offer a venue for open discussion and to juxtapose written work without regard to style and without deferring to the restrictions of university based journals, and they hope to be able to articulate something of the common sense of the new age before us. Common Sense does not have any political programme nor does it wish to define what is political in advance. Nevertheless, we are keen to examine what is this thing called “common sense”, and we hope that you who read the journal will also make contributions whenever you feel the inclination. We feel that there is a certain imperative to think through the changes before us and to articulate new strategies before the issues that arise are hijacked by the Universities to be theories into obscurity, or by Party machines to be practised to death.

Why ‘Common Sense’?

The editorial in issue five, which you can read below, discusses why the journal was named, ‘Common Sense’.

Hopefully, if you’re new to Common Sense, like me, this has whetted your appetite for the journal and you’re looking forward to seeing it in digital form. In the meantime, you might want to read some of the work published elsewhere by members of the collective, such as Werner Bonefeld, John Holloway, Richard Gunn, Richard Noris, Alfred Mendes, Kosmas Psychopedis, Toni Negri, Nick Dyer-Witheford, Massimo De Angelis and Ana Dinerstein. If you were reading Common Sense back in the 1990s, perhaps contributed to it in some way and would like see Common Sense in digital form so that your students can read it on their expensive iPads and share it via underground file sharing networks, please have a dig around for those issues I’m missing and help me get them online.

Cheers.

Common Sense

The journal Common Sense exists as a relay station for the the exchange and dissemination of ideas. It is run on a co-operative and non-profitmaking basis. As a means of maintaining flexibility as to numbers of copies per issue, and of holding costs down, articles are reproduced in their original typescript. Common Sense is non-elitist, since anyone (or any group) with fairly modest financial resources can set up a journal along the same lines. Everything here is informal, and minimalist.

Why, as a title. ‘Common Sense’? In its usual ordinary-language meaning, the term ’common sense’ refers to that which appears obvious beyond question: “But it’s just common sense!”. According to a secondary conventional meaning, ‘common sense’ refers to a sense (a view, an understanding or outlook) which is ‘common’ inasmuch as it is widely agreed upon or shared. Our title draws upon the latter of these meanings, while at the same time qualifying it, and bears only an ironical relation to the first.

In classical thought, and more especially in Scottish eighteenth century philosophy, the term ‘common sense’ carried with it two connotations: (i) ‘common sense’ meant public of shared sense (the Latin ‘sensus comunis‘ being translated as ‘publick sense’ by Francis Hutcheson in 1728). And (ii) ‘comnon sense’ signified that sense, or capacity, which allows us to totalise or synthesise the data supplied by the five senses (sight, touch and so on) of a more familiar kind. (The conventional term ‘sixth sense‘, stripped of its mystical and spiritualistic suggestions, originates from the idea of a ‘common sense’ understood in this latter way). It is in this twofold philosophical sense of ‘common sense’ that our title is intended.

Continue reading “Digitising Common Sense. Journal of the Edinburgh Conference of Socialist Economists”