Richard Hall and I are presenting at the OpenEd10 conference next week. Here’s a few slides that Richard has just put together. The paper can be downloaded here.

UPDATE: Here’s the video recording of our session. We ditched the slides.

Richard Hall and I are presenting at the OpenEd10 conference next week. Here’s a few slides that Richard has just put together. The paper can be downloaded here.

UPDATE: Here’s the video recording of our session. We ditched the slides.

My presentation for the RSP event: Doing it differently. No slides, just a live demo using the outline below.

1. WordPress is an excellent feed generator: https://joss.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2009/04/15/addicted-to-feeds/ 2. It's also an excellent, personal, scholarly CMS https://joss.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2009/08/25/scholarly-publishing-with-wordpress/ 3. If you have an RSS feed, you can create other document types, too https://joss.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2010/01/04/creating-a-pdf-or-ebook-from-an-rss-feed/ 4. We conceived a WordPress site as a document (and a WordPress Multisite install as a personal/team/dept/institutional multi-document authoring environment) http://jiscpress.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk http://jiscpress.org 5. Here's my MA Dissertation as a WordPress site using digress.it http://tait.josswinn.org/ 6. WordPress allows you to perform certain actions on feeds, such as reversing the post/section order http://tait.josswinn.org/feed/?orderby=post_date&order=ASC 7. EPrints allows you to 'capture' data from a URI http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/2004/ 8. Suck it into your feed reader, for storage/reading - it's searchable there, too. https://www.google.com/reader/view/feed/http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/2004/2/index.html%253Forderby%253Dpost_date%2526order%253DASC 9. And use another service to create an ebook or PDF version http://www.feedbooks.com/news 10. RSS. Loosely joined services: Author: WordPress --> Preserve: EPrints --> Read: GReader Feedbooks etc... 11. p.s. How about using EPrints to drive a WordPress site, too? Why extend a perfectly good preservation and storage application to include web 2.0 features, when it can be used to populate a cutting edge CMS with repo data?

Michael Albert is visiting the university later this month. Below are details of his class and public seminar. I’m looking forward to meeting him. I doubt he’ll remember the few months I spent volunteering as an editor of one of Z-Net’s web pages, back in 2000. I tried to impose standards-based XHTML onto their then, M$ FrontPage ‘driven’ website and lost the battle 😉

Journalism Research Seminar Series, Lincoln School of Journalism

Basics of independent media organisation and production

Seminar room MC 0024, Ground floor MHAC-Building, Brayford Pool Campus, 4-6pm on 27 October, 2010

School of Social Sciences Seminar Series

PARECON – Life After Capitalism

Jackson Lecture Theatre, Ground floor, Main Building, Brayford Pool Campus, 7.30-9.30pm on 27 October, 2010 Talk is open to the public

For further info and speaking dates of Michael Albert in the UK see: http://www.ppsuk.org.uk/matour/

Michael Albert is a longtime political and media activist with a tremendous record. He has authored 15 books and published widely on topics such as radical politics, economics, social change, peace and media. Furthermore, he is known for developing participatory economics (PARECON), an alternative model to capitalism and socialism. He cofounded the Boston (USA) based book publisher South End Press and the independent media platform ZCommunications. Until today, South End Press and Z have published works from renowned authors including Arundhati Roy, Noam Chomsky, John Pilger, Amy Goodman, Dahr Jamail, Robert Fisk, Vandana Shiva, Edward S. Herman and Howard Zinn.

In his first talk, eminent US social critic Michael Albert will reflect on more than 30-years experience working in non-profit, alternative media organisations. The talk will focus on issues such as how to finance non-profit media in a capitalist/market system, how to develop online media and how to structure an organisation to be truly participatory and democratic. Albert will do examine ways of how to cope with economic and political challenges and how students and non-professionals can produce and distribute independent media. The talk will be followed by Q&As.

His second talk (followed by Q&As) will be particularly interesting for everyone seeking a more just and peaceful world. This is what you can expect:

PARECON – Life After Capitalism

Today’s capitalist system has brought with it war, economic crisis, ecological decay, massive wealth inequality, alienation, authoritarianism and social breakdown. Are these problems inevitable, or could they be overcome in a different system? And if so, how? These issues, perhaps for the first time in history, have become a matter of survival.

Michael Albert, co-author of ‘ParEcon: Life After Capitalism’, co-founder of ZCommunications and leading US social activist will present ‘Participatory Economics’, a Vision for a type of democratic economy based on equitable co-operation that is put forward as an alternative to capitalism and also to other 20th century systems that have gone under the label ‘socialism’. It includes new institutions that seek to foster self-management, equity, diversity and solidarity. Parecon is a direct and natural outgrowth of hundreds of years of struggle for economic justice as well as contemporary efforts with their accumulated wisdom and lessons.

Dougald Hine, co-founder of The School of Everything, has been invited by the Centre for Educational Research and Development to talk about his experience in setting up and running The School of Everything. He will be speaking at 3pm on October 13th, MB1010.

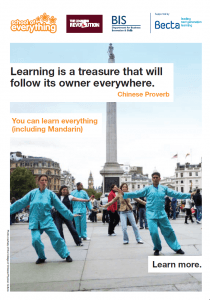

The School of Everything is an award winning ‘free school’ for the 21st century, using the Internet to connect people who want to teach with people who want to learn. It’s aim is to allow people to design their own education. In 2010, School of Everything was chosen by Becta and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills as its new platform for adult informal learning in the UK.

The School of Everything is an award winning ‘free school’ for the 21st century, using the Internet to connect people who want to teach with people who want to learn. It’s aim is to allow people to design their own education. In 2010, School of Everything was chosen by Becta and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills as its new platform for adult informal learning in the UK.

Douglad will be speaking informally about how the School of Everything came about and how he sees it connecting to the wider relationship between technology, institutions and education.

I am particularly interested in talk to Dougald about our idea for a Social Science Centre and hope that we can learn from his efforts to engage people in creating their own education. On a different note, I’m also interested in talking to him about his work on The Dark Mountain Project and the role of education in crafting new stories for the future.

Not a post about my own work but that of my colleague, Mike Neary, who leads the Centre for Educational Research and Development (CERD), where I work. When I first joined the University of Lincoln, Mike asked me to contribute to a book chapter he was writing on the Student as Producer (read it here). More recently, Student as Producer has become a major university project, funded by the HEA. The project aims to

…establish research-engaged teaching and learning as an institutional priority at the University of Lincoln, making it the dominant paradigm for all aspects of curriculum design and delivery, and the central pedagogical principle that informs other aspects of the University’s strategic planning.

Underlying the practical ambitions of the project are a number of theoretical ideas, which draw from critical social theory. Recently, Mike has written about these in his paper, Student as Producer: A Pedgogy for the Avant-Garde and another book chapter, Pedagogy of Excess: An Alternative Political Economy of Student Life, authored with Andy Hagyard, who also works in CERD.

Pedagogy of Excess looks to the world-wide social protests of 1968, in which students played a central role, for inspiration for the notion of research-engaged teaching. Grounded in critical social theory and based on historical material that deals with the events in Paris, Pedagogy of Excess describes 1968 as a moment when the students became more than students, and acted as revealers of a general crisis by demystifying the process of research. The students did this by engaging in various forms of theoretical and practical activity that took them beyond the normal limits of what is meant by higher education. It is the notion of students becoming more than students through a radical process of revelation that provide the basis for our concept of Pedagogy of Excess. At the end of the chapter we discuss Pedagogy of Excess in relation to other critical pedagogies, and set out a curriculum based on the principles of pedagogical excess. ((Download pre-print of book chapter here))

Both the journal article and book chapter focus on a radical re-conceptualisation of what it means to teach and learn. I found them really stimulating and I hope you do, too.

I’m starting to write a book chapter on Open Education and have been thinking about its meaning as a movement, like other social movements. Earlier today, I was reading The Rocky Road to a Real Transition. The Transition Town’s Movement and What it Means for Social Change. This is a constructive critique of the Transition Towns movement. I recommend reading the ‘Rocky Road’ booklet as it asks a number of questions that are applicable to any movement that advocates positive social change. From reading the booklet, I’ve pulled out some questions we might similarly ask of the Open Education movement. What do you think? I’ll try to offer some answers in this book chapter I’m writing…

I have a Kindle 3 (wifi only). Here’s what I think about it after two weeks. I should say that I have absolutely no interest in reading eBooks bought from Amazon on it. What interests me is the ability to read newspapers and academic articles on it.

+ Size, weight and general form are good. Feels nice to hold. I also have the leather case for it, but it doubles the weight and is awkward to hold so I only use it when the Kindle is shoved into my bag.

+ The screen is excellent for reading text in the .mobi and native amazon format. I appreciate the ability to change the font size more than I imagined I would and have found myself wishing that I could change the font size on print books now. The screen appears sharper the more light that is shining on it (i.e. daylight) but is unreadable in poor light/darkness (much like a book).

– Despite the screen being the main strength of the Kindle, looking at a grey scale screen still feels like a distinct step backwards. I’m reminded of using my mid-90s laptop. Page turns/screen refreshes are about as fast as turning a page in a print book, which sounds satisfactory but the experience is all wrong. Page turns are clearly visible screen refreshes/flashes.

– The speed of the device feels retrograde. My touch screen phone feels faster despite having roughly the same 500MHz processor speed.

+ Having said that, from an engineering point of view, the device is apparently a thing of beauty. I can appreciate that.

– The screen is poor for reading A4 sized PDF files. It’s just not big enough and the font on a full page view is too small. On landscape mode, it is better but requires lots of button pressing to scroll through the text and is generally not worth the bother because…

+ You can email .doc and .pdf files (and other text formats) to your @kindle.com or @free.kindle.com email address and Amazon will immediately send you a nicely formatted conversion of the PDF to your device.

+ Feedbooks is a nice way to get out of copyright (i.e. classics) books on the Kindle for free.

– All content is homogenized to become ‘Kindle Content’. Newspapers, books, articles, whatever they originally might have looked like, become the same standardised text on the screen, surrounded by a dull graphite border. I tried to tell myself that it strips away the fluff to reveal the true essence of the book/newspaper/article, but I find the experience of reading otherwise creatively designed content (i.e. a newspaper) on the Kindle quite dispiriting. Even images become washed out and gray. Thankfully, for academic papers, it doesn’t matter so much because they tend to include little more than text in the first place.

+ The battery life is excellent. Over a week with wifi turned on all the time. Apparently a month if turned off, but that’s not how I use it.

– The 3.0 software was very unstable and the device froze regularly. However…

+ The 3.0.1 software upgrade fixes any software issues I experienced.

-/+ The browser is OK. Mobile sites are bearable. I would usually choose using my touch screen phone to browse the web over the Kindle. Web browsing on a slow device with a black and white screen isn’t much fun. However, the ‘Article Mode’ option, which is based on the same idea as Readability, is a nice touch and makes reading a long article a pleasure. Better than using my phone or my laptop or PC. I was already in the habit of saving long print view versions of articles on the web to PDF for reading and now I can email them to my Kindle to read or browse to the web page on the Kindle itself.

-/+ The keyboard is OK. I wish there were keys for numbers. Initially I found the keyboard awkward and navigation around the device and content, a hassle. I’ve got used to it and it’s beginning to make sense to me now. It’s no match for touch screen navigation on the iPhone or Android phones though. The keyboard buttons make a noise so it’s irritating if you’re in a quiet room (i.e. reading in bed with your partner).

– It’s linked to my Amazon account and so it’s yet another device I have to password protect. I hate the fact that I have to login to the device just to read something.

– The annotation and sharing features are very basic. You can make notes on selected text using the fiddly keyboard but it’s no match whatsoever for the convenience of scribbling in the margins with a pencil. Sharing to Twitter simply tweets a note and link to some selected text on an Amazon web page. I would much prefer a ‘share by email’ feature, like I have on my phone, so I could send myself or others, annotated text by email.

– I wish I had the 3G version. There are times when logging into wifi or having no wifi at all is a minor inconvenience. I thought I’d be able to tether it to my phone but the Kindle wifi won’t work with enterprise/P2P wifi networks. Given the cost, I would trade the leather case for the addition of 3G.

+ Calibre is a fantastic bit of open source software for creating newspapers and delivering them to your device. I have it set up so that my laptop at home wakes at 6am, opens Calibre, downloads three newspapers and sends them to my Kindle ready for when I wake up at 6.30ish. The papers are nicely formatted, with images, and easy to read on the way to work. This somewhat makes up for the complaint about homogenized content I mentioned above. You can pay for Amazon to deliver newspapers to you, too, but by most accounts I’ve seen, they are poorly presented and expensive compared to the print editions. Why bother when Calibre does it for you (and much more)?

– I haven’t used the text-to-speech feature yet. The music player on it is very basic. It’s like using an iPod Shuffle. Stop, start, forward, backwards.

– Already having a smart phone, iPod Touch, home laptop, work laptop and work desktop, the Kindle is an improvement in some areas (straight forward reading of natively formatted text), but is yet another device to throw in my bag. I was sat at a conference recently with my phone, laptop and Kindle all at hand, feeling like a bit of an idiot.

I came across a post by David Wiley the other day, concerning MIT’s OpenCourseWare initiative and it got me thinking about MIT and OER in general…

I would like to suggest that OER can be viewed as another example of the mechanisation of human work, which seeks to exploit a greater amount of collective abstract labour-power while reducing the input and therefore reliance on any one individual’s concrete contribution of labour. It’s important to understand what is meant by abstract labour and how it relates to the creation of value, which we’ll see is at the core of MIT’s OCW plans for sustainability. Wendling provides a useful summary of how technology is employed to create value out of labour.

Any given commodity’s value can be seen either from the perspective of use or from the perspective of exchange: for enjoyment consumption or for productive consumption. Likewise, any given worker can be seen as capable of concrete labor or abstract labor-power. Labor is a qualitative relation, labor-power its quantitative counterpart. In capitalism, human labor becomes progressively interchangeable with mechanized forces, and it becomes increasingly conceptualized in these terms. Thus, labor is increasingly seen as mere labor-power, the units of force to which the motions of human work can be analytically reduced. In capitalism, machines have labor-power but do no labor in the sense of value-creating activity. ((Amy Wendling (2009) Karl Marx on Technology and Alienation. p. 104))

The use of technology in attempts to expand labour’s value creating power is central to the history of capitalism. From capitalism’s agrarian origins in 16th century England, technology has been used to ‘improve’ the value of private property. In discussing value, we should be careful not to confuse it simply with material wealth, which is a form of value expressed by the quantity of products produced.

Marx explicitly distinguishes value from material wealth and relates these two distinct forms of wealth to the duality of labor in capitalism. Material wealth is measured by the quantity of products produced and is a function of a number of factors such as knowledge, social organization, and natural conditions, in addition to labor. Value is constituted by human labor-time expenditure alone, according to Marx, and is the dominant form of wealth in capitalism. Whereas material wealth, when it is the dominant form of wealth, is mediated by overt social relations, value is a self-mediating form of wealth. ((Postone (2009), Rethinking Marx’s Critical Theory in History and Heteronomy: Critical Essays, The University of Tokyo Centre for Philosophy, p. 40))

MIT’s OpenCourseWare initiative provides a good example of how Open Education, currently dominated by the OER commodity form, is contributing to the predictable course of the capitalist expansion of value. Through the use of technology, MIT has expanded its presence in the educational market by attracting private philanthropic funds to create a competitive advantage, which has yet to be surpassed by any other single institution. In this case, technology has been used to create value out of the labour of MIT academics who produce lecture notes and lectures which are then captured and published on MIT’s corporate website. In this process, value has been created for MIT through the application of science and technology, which did not exist prior to the inception of OCW in 2001. The process has attracted $1,836000 of private philanthropic funding, donations and commercial referrals. In 2009, this was 51% of the operating costs of the OCW initiative, the other 49% being contributed by MIT. ((See David Wiley’s blog post on MIT’s financial statement))

In terms of generating material wealth for MIT, it is pretty much breaking even by attracting funds from private donors, but the value that MIT is generating out of its fixed capital of technology and workers should be understood as distinct from its financial accounts. Through the production of OERs on such a massive scale, MIT has released into circulation a significant amount of capital which enhances the value of its ‘brand’ (later I refer to this as ‘persona’) as educator and innovator. Furthermore, through the small but measurable intensification of staff labour time by the OCW initiative, additional value has been exorted from MIT’s staff, who remain essential to the value creating process but increasingly insignificant as individual contributors. As a recent update from MIT on the OCW initiative shows, ((OpenCourseWare: Working Through Financial Changes)) following this initial expansion of “the value of OCW and MIT’s leadership position in open education” and with the private philanthropic funding that has supported it due to run out, new streams of funding based on donations and technical innovation are being considered to “enhance the value of the materials we provide.” As the report acknowledges, innovation in this area of education has made the market for OER competitive and for MIT to retain its lion’s share of web traffic, it needs to refresh its offering on a regular basis and seek to expand its educational market footprint. Methods of achieving this that are being discussed are, naturally, technological: the use of social media, mobile platforms and a ‘click to enroll’ system of distance learning. Never mind that the OERs are Creative Commons licensed, ‘free’ and, notably, require attribution in order to re-use them, the production of this value creating intellectual property needs to be understood within the “perpetual labour process that we know better as communication.” ((Söderberg, Johan (2007) Hacking Capitalism. The Free and Open Source Software Movement, p. 72)) Understood in this way, the commodification of MIT’s courses occurs long before the application of a novel license and distribution via the Internet. OCW is simply “a stage in the metamorphosis of the labour process”. ((Soderberg, 2007, p. 71)).

MIT’s statement concerning the need to find new ways to create value out of their OCW initiative is a nice example of how value is temporally determined and quickly falls off as the production of OERs becomes generalised through the efforts of other universities. Postone describes this process succinctly:

In his discussion of the magnitude of value in terms of socially-necessary labor-time, Marx points to a peculiarity of value as a social form of wealth whose measure is temporal: increasing productivity increases the amount of use-values produced per unit time. But it results only in short term increases in the magnitude of value created per unit time. Once that productive increase becomes general, the magnitude of value falls to its base level. The result is a sort of treadmill dynamic. On the one hand, increased levels of productivity result in great increases in use-value production. Yet increased productivity does not result in long-term proportional increases in value, the social form of wealth in capitalism. ((Postone, 2009, p. 40))

Seen as part of MIT’s entire portfolio, the contribution of OCW follows a well defined path of capitalist expansion, value creation and destruction and also points to the potential crisis of OER as an institutional commodity form, being the dimunition of academic labour, which is capitalism’s primary source of value, and the declining value of the generalised OER commodity form, which can only be counteracted through constant technological innovation which requires the input of labour. As Wendling describes, this is part and parcel of capitalism, to which OER is not immune.

Scientific and technological advances reduce the necessary contribution of living labor to a vanishing point in the production of basic commodities. Thus, they limit the main source of the capitalist’s profit: the exploitation of the worker. This shapes the capitalist use of science and technology, which is a use that is politicized to accommodate this paradox. In this usage, the introduction of new machinery has two effects. First, the machine displaces some workers whose functions it supplants. Second, the machine heralds a step up in the exploitation of the remaining workers. The intensity and length of their working days are increased. In addition, as machinery is introduced, capital must both produce and sell on an increasingly massive scale. Losses from living labor are recompensed by the multiplication of the small quantities of remaining labor from which value can be extorted. In all of these ways, capitalism and technological advancement, far from going hand in hand, are actually inimical to one another, and drive the system into crisis. In this respect, a straightforward identification of constantly increasing technicization with capitalism misses the crucial dissonance between the two forces. ((Wendling 2009, p.108))

The example of MIT given above is not intended to criticise any single member of the OCW team at MIT, who are no doubt working on the understanding that the initiative is a ‘public good’ – and in terms of creating social wealth, it is a public good. My suggestion here is to show how seemingly ‘good’ initiatives such as OCW, also compound the social relations of capitalism, based on the exploitation of labour and the reification of the commodity form.

Furthermore, being the largest single provider of ‘Open Education’, MIT’s example can be carried over into a discussion of the Open Education movement’s failure to provide an adequate critique of the institution as a form of company and regulator of wage-work.

As Neocleous has shown, ((Neocleous, Mark (2003) Staging Power: Marx, Hobbes and the Personification of Capital)) in modern capitalism the objectification of the worker as the commodity of labour serves to transform the company into a personified subject, with greater rights under, and fewer responsibilities to, the law than people themselves. As the university increasingly adopts corporate forms, objectives and practices, so the role of the academic as abstract labour is to improve the persona of the university. Like many other US universities, MIT award tenure to academics who are “one of the very tiny handful of top investigators in your field, in the world” thus rewarding but also retaining through the incentive of tenure, staff who bring international prestige to MIT. ((Unraveling tenure at MIT)) Through an accumulation of “top investigators”, effort and attention is increasingly diverted from individual achievement and reputation to the achievements of the institution, measured by its overall reputation, which is rewarded by increased government funding, commercial partnerships and philanthropic donations. This, in turn, attracts a greater number of better staff and students, who join the university in order to enjoy the benefits of this reward. Yet once absorbed into the labour process, these individuals serve the social character of the institution, which is constantly being monitored and evaluated through a system of league tables.

“…the process of personification of capital that I have been describing is the flip side of a process in which human persons come to be treated as commodities – the worker, as human subject, sells labour as an object. As relations of production are reified so things are personified – human subjects become objects and objects become subjects – an irrational, “bewitched, distorted and upside-down world” in which “Monsieur le Capital” takes the form of a social character – a dramatis personae on the economic stage, no less.” ((Neocleous, 2003, p. 159))

To what extent the Open Education movement can counteract this personification of educational institutions and the subtle objectification of their staff and students, is still open to question, although the overwhelming trend so far is for OER to be seen as sustainable only to the extent that it can attract private and state funding, which, needless to say, serves the reputational character (a significant source of value, according to Neocleous) of the respective universities, as institutions for the ‘public good’. Yet, as Postone has argued, the creation of this temporally determined form of value is achieved through the domination of people by time, structuring our lives and mediating our social relations. The increased use of technology is, and always has been, capitalism’s principle technique of ‘improving’ the input ratio of labour-power measured abstractly by time, to the output of value, which is itself temporal and therefore in constant need of expansion. And so the imperative of conjuring value out of labour goes on…