Last night, I submitted two bids to JISC’s Infrastructure for Education and Research programme and, having submitted a few bids to JISC over the last year or so, I wanted to jot down a few thoughts about my experience bidding for funding. Maybe it mirrors your experience, too. I’d be interested to know. Like every other bid I’ve written, you can read them online if you like:

JISCPress (Google doc) – Awarded £26K

JISCPress Benefits & Realisation Tender (Google doc) – Awarded £10K

ChemistryFM (PDF) – Awarded £18K

Powering Down? – Not funded. Read the judges positive comments in the postscript of this blog post.

Total ReCal (Google doc) – Awarded £28K

I might also add our Talis bid, which could just as easily have been a JISC bid. It was not funded but the judges liked it.

And the latest two:

Linking You << get it? ‘Lincoln U’ 🙂 (Google doc) UPDATE: Awarded £14K

Like most other HEIs, Lincoln’s web presence has grown ‘organically’ over the years, utilising a range of authoring and content management technologies to satisfy long-term business requirements while meeting the short-term demands of staff and students. We recognise the value of our .ac.uk domain as an integral part of our ‘Learning Landscape’ and, building on recent innovations in our Online Services Team, intend to re-evaluate the overall underlying architecture of our websites with a range of stakeholders and engage with others in the sector around the structure, persistence and use of the open data we publish on the web. Some preliminary work has already been undertaken in this area and we wish to use this opportunity to consolidate what we have learned as well as inform our own work through a series of wider consultations and engagement with the JISC community.

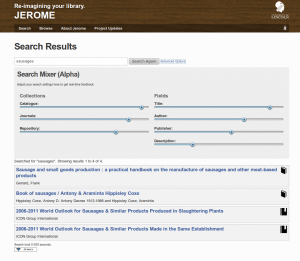

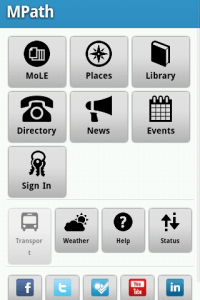

Jerome (Google doc) UPDATE: Awarded £36K

Jerome began in the summer of 2010, as an informal ‘un-project’, with the aim of radically integrating data available to the University of Lincoln’s library services and offering a uniquely personalised service to staff and students through the use of new APIs, open data and machine learning. Jerome addresses many of the challenges highlighted in the Resource Discovery Taskforce report, including the need to develop scale at the data and user levels, the use of third-party data and services and a better understanding of ‘user journeys’. Here, we propose to formalise Jerome as a project, consolidating the lessons we have learned over the last few months by developing a sustainable, institutional service for open bibliographic metadata, complemented with well documented APIs and an ‘intelligent’, personalised interface for library users.

At this point, I should give a few words of appreciation to Paul Stainthorp, Alex Bilbie, Nick Jackson, Chris Goddard and David Young, who helped me put these recent bids together. In particular, Paul worked with me on and off over the weekend to finish off the Jerome bid and it is all the better for it. And that brings me on to the first point I want to make about working with people.

Open bid writing

I don’t have that much experience raising funds. I wrote my first bid (JISCPress) in April last year with Tony Hirst, at the Open University, who I didn’t really know at the time but has since become a friend and I am now Co-Director of a not-for-profit company with him. The JISCPress project was based on some fun we were having outside of work to try to open up the way that the government consulted with the public. As you can see from the bid, we simply wrote up the ideas we were having based on our trials and errors with WriteToReply. Because of the nature of the project, we wrote the bid in public, inviting anyone to contribute or simply observe. We told lots (hundreds? thousands?) of people we were doing this through our online networks. It was liberating to write it in this way and we’ve since been commended by staff at JISC for taking this approach. Some seasoned bid writers were quite surprised that we would do such a thing, but Tony and I wanted to make a point that bid writing could be an inclusive and collaborative endeavour, rather than a secretive and competitive exercise. Neither of us felt like we had anything to lose by working in this way. It was my first bid and raising funds was not something expected of me at the time (hang on?! it’s still not in my job description! 😉 )

Anyway, we got the funding and then some more funding and the award winning outcomes of the project are now in use by JISC and hundreds of other people. I continue to work on it with the original team, despite the period of funding being over.

I still write most of my bids online and in public, but I don’t shout about it these days. After I was funded once, the pressure to repeat the process has, alas, made me more cautious and frankly I hate this. I still publish and blog about the bids I’ve made shortly after they’ve been submitted, but I’ve not quite repeated the openness and transparency that Tony and I attempted with JISCPress. Shaun Lawson, a Reader in Computer Science, and I replied to the Times Higher about this subject last week suggesting that there is much to be gained from open bid writing. ((“We read with interest the suggestion by Trevor Harley (“Astuteness of crowds”; 4th November 2010) that the peer review of grant applications could be replaced by crowdsourcing. We suggest going even further in this venture of harnessing the potentially limitless cognitive surplus of the academy (apologies to John Duffy “Academy Untoward” also 4th November 2010) and crowdsourcing the process of authoring the grant proposal itself. Our reasoning is that, given enough wisdom from the idling academic crowd, an individual proposal could be ironed completely free of half-baked rationales, methodological flaws, over-budgeted conference travel and nebulous impact statements and would, therefore, be guaranteed a place near the top of any ranking panel. On a serious note, we do believe there is much to be gained by both applicants and funders adopting a more transparent, collaborative and open grant bidding process, in which researchers author a funding proposal collectively and in public view using, for instance, wikis or Google docs. Indeed, we have ourselves successfully piloted such an approach (http://lncn.eu/r23), which mirrors the more positive aspects of the ‘sandpit’ experience, and unreservedly recommend it to other researchers.”)) I recall, also, that in a podcast interview, Ed Smith, the Deputy Chairman of HEFCE warned that competition in the bidding process might better be replaced with more collaborative submissions in the future as funding gets tighter.

I know there are staff in JISC that really do favour this approach, too, and I wonder whether JISC, advocates of innovation in other institutions, might attempt to innovate the bid writing process by requiring that all bids received must demonstrate that they have been written openly, in public and genuinely solicited collaboration in the writing process. We are all used to submitting bids with partners and collaborative bid writing is quite the norm behind closed doors, but why not require that the bid writing is collaborative and open, too? JISC could at least try this with one of their funding calls and measure the response.

From ‘un-projects’ to projects

The other point I want to make is the value of being able to write bids that are simply a formalisation of work we’ve already started. There must be few things more soul destroying that being asked to look at the latest funding programme and conjure up a project to fit the call (I don’t do it). Like JISCPress, all the other bids that I’ve been successful in receiving funds for were based on work (actually, better described as ‘fun’) that we’d been doing in our ‘spare time’, evenings and weekends. We were, in effect, already doing the projects and when the right funding call came up, we applied to it, demonstrating to JISC that we were committed to the project and offering a clear sense of the benefits to the wider community. JISCPress was based on WriteToReply, ChemistryFM was based on my work on the Lincoln Academic Commons, Total ReCal, Jerome and Linking You are all based on a variety ((Jerome has its own blog, and we all blog regularly about work we’re doing.)) of work that Alex, Nick, Paul and, to a lesser extent I, have been doing in between other work. What’s worth underlining here is that we’re fortunate to have Snr. Managers at the University of Lincoln, who support us and encourage a ‘labs’ approach to incubate ideas. Inevitably, it means that we end up working outside of our normal hours but that because we’re interested in the work we’re doing and when a funding call comes up and it aligns with our work, we apply for it. As you know, to ‘win’ project funding is an endorsement of your work and ideas and it confirms to us and, importantly, to Snr. Management, that working relatively autonomously in a labs environment can pay off.

A supportive environment

Up to now, I’ve tried to make the point that when I write a bid, it is a somewhat open, collaborative process that proposes to formalise and build on work that we’re already doing and what we already know. I know that this is not uncommon and is not a guaranteed ‘secret to success’, but it is worth underlining. Finally, I want to acknowledge the wider support I receive from colleagues at the university, in particular from David Young and Annalisa Jones in the Research Office. I know from talking with people in other institutions that often, the bid writers remain responsible for putting the budget together (no simple task) and have to jump through bureaucratic hoops to even get the go ahead for the bid and then find a senior member of staff who will sign the letter of support. Fortunately, in my experience at Lincoln it is quite the opposite. I have very little to do with pinning down the budget. I go to the Research Office for 30 mins, explain the nature of the project, the amount we can bid for and the kind of resources we will need and a day or so later, I am provided with the budget formatted in JISC’s template. Likewise, the letters of support are turned around in a matter of hours, too, leaving me to focus on the bid writing. There is never any question of whether I should submit a bid or not as I’m trusted to be able to manage my own time and likewise, the other people involved in the projects are trusted too. Of course, we discuss the bids with our managers while writing them and if they are concerned with the objectives or the amount of time we might be committing to the project, they are able to say so, but because we write bids that are based on work we’re already doing, it’s much easier to know whether a bid is viable.

So that’s how it’s worked for me so far. I sent off two bids last night and I felt they were the strongest I’ve submitted so far, not least because of all the work that Paul, Alex and Nick have been doing. Frankly, neither of these bids would have been written were it not for their good work so far and their energy and enthusiasm for ‘getting stuff done’. Of course it will be nice if one or both bids are funded but the process of writing formally about the work we are doing is a worthwhile process in itself, as it helps to situate it in the wider context of work at the university and elsewhere. Now, the bids are in it’s time to relax a bit and get on with something else.